Stories from our Brothers that walked the walk.

Our Dusters and Quad 50s had excellent fields of fire, commanding all avenues of approach to the northern perimeter of the base. Our two Duster positions were well located at opposite ends of the runway with the Quad 50s placed in between but not more than one hundred meters away from a Duster. All weapons had excellent fields of fire, commanding all avenues of approach to the northern perimeter of the base.

My Quad 50 was providing cover fire from across the river when a Marine officer came up to me and asked, “Sarge, my men are getting the hell shot out of them, can you help them out?” I looked at the other guys on the truck (Harris, Davis, the gunner, and David the driver), and they looked at me and shrugged. There was never any thought to say “No”, but I think that each of us told ourselves that we weren’t going to make it back from this one. I said “Let’s Go”.

I had never heard of the hot pursuit doctrine, but the plan sounded good to me. I and most of the Duster crews were fairly bored with the routine and going into the DMZ sounded like a serious adventure. But I knew that going into the DMZ was not a decision a first lieutenant could make alone.

24 HOURS OF FACE-TO-FACE, HAND-TO-HAND FIGHTING AGAINST 12,000 ENEMY SOLDIERS

A SMALL CONTINGENT OF DUSTERMEN AND MARINES TURN THE TIDE OF BATTLE

The following story in the most accurate account of the battle taken from my diary and interviews with the combatants. We Dustermen have never openly spoken about it except with those who were in the battle. You will be reading the “no holds barred” collective experiences of a handful of “Dustermen” and Marines who fought ferociously in one the biggest, most horrific, under reported, battles in the Vietnam War.

It is one of the many unsung stories of “Charlie Battery” 1st Battalion, 44th Artillery, (Automatic Weapons) (Self Propelled); a humble attempt at an “After Action Report” that conveys the selfless sacrifices and the heroism displayed by our “Duster and Marine Brothers” on that day.

The following 685 page photo gallery is a year in the life of 1st Battalion 44th Artillery Twin 40mm Duster crews from Charlie Battery, Alpha Battery and Battery G-65th – Quad 50 Artillery crews and all the Marines units who fought along side each other in combat along the “DMZ” and south to Hue City, Vietnam. A time period from August 1967 to August 1968.

My Duster-still in the rear of our position, where it had been ordered at the beginning of the fight to cover the back of the task force-was in a clearing partially enclosed by a large thicket of elephant grass. A tank sent from Firebase C-3 to assist with the withdrawal had arrived and stopped about 20 yards to my right, but as soon as it pulled up an RPG arced out from the elephant grass thicket and hit the turret, sending up a shower of white sparks.

The superstitious VC are often baffled, frightened and beaten by one of the most effective weapons in the 9th Infantry Division’s arsenal of mobile death-dealers –the “Duster.”

“The VC call them ‘Fire Dragons’ because they don’t know what to make of them,” explained First Lieutenant Gene S. Lucas, Executive Officer of Battery C of the 5th Battalion, 2nd Artillery who support the ‘Old Reliables’ with the armored artillery pieces.

The Duster’s biggest shortcoming is its inability to negotiate the deep Delta mud of the rainy season. Twenty-five tons of armored track is also hard pressed to cross several of the Delta’s weaker bridges “We’re waterborne much of the time,” explained SSG Patrick Webster. “The Dusters can’t be airlifted, and this is probably the best way to move them.” Floating on the canals, the Dusters also serve another purpose. Working with M-8 landing craft, the Dusters cruise up and down the myriad of Delta rivers and canals, firing at intelligence targets. Intelligence targets and radar sighing have proven lucrative for the “Have Guns Will Travel” crews. “We rely heavily on radar and intelligence reports,” Lucas, noted, “They’re usually right on the nose.'”

“I am recording these personal recollections so that I could document these events and my feelings during my tour of duty. Very little else has been said or written about these early battles. The following stories are but a few of what happened back in 1966 and 1967. I hope you enjoy them.”

Note: Paul Gronski’s chronicles were recovered from the old archived NDQSA.COM website 11 March 2024 RCBurmood

Further information about the Battle for Con Thien.

“Hill of Angels”, U.S. Marines and the Battle for Con Thien q967-1968, Joseph C. Long USMC

A monograph prepared as part of the Marines in the Vietnam War Commemorative Series

In November 1968 the First Vulcan Combat Evaluation Team was formed at Fort Bliss and sent to Vietnam to test the suitability of the Vulcan ADA weapon system for ground support. This Air Defense Trends October 1969 article describes the ferocity of enemy attack and the still greater ferocity of the U.S. Army forward area weapons response – the Vulcan in particular. CPT Wilson was killed during a rocket attack on Long Binh Base Camp on 23 Feb 1969.

Max Whittington served in Headquarters Company, 6th Battalion, 71st Artillery (Hawk Missiles). He was with the unit when it left Ft. Bliss, Texas, and traveled by troop ship–the General Hugh J. Gaffey–to Viet Nam, in September of 1965. His story is primarily of day-to-day activity. A note of interest was the impact Vietnam weather had on Hawk missile serviceability.

Memo: This story was recovered from the old archived NDQSA.COM website 11 March 2024 RCBurmood

Originally published as a 6 part series.

In 1968 I was a SP4 with Headquarters Battery, 6th Battalion, 56th Artillery, one of the two HAWK missile battalions serving in Vietnam. My MOS was 16K20 (Fire Distribution Crewman) but by 1968 there was little need for antiaircraft protection around Saigon and for that matter any place else in Vietnam.

Although trained only on missiles, my primary job at the 6/56th was security, as I was part of a field reactionary force team. We did everything including perimeter defense, convoy security, civic duty, and ground sweeps outside the perimeter. This is my personal recollection of the VC/NVA attack on the Long Binh area during the 1968 Tet Offensive around Saigon, specifically the incident referred to at the Battle of Widow’s Village.

Further information about the Battle fat Widows Village

For more information about the Battle at Widows Village please read this article by CPT Amauld Fleming first published on a defunct 9th Infantry Division website and now archived here.

the Battle at Widows Village _CPT Fleming 9thID

Memo: MSG Larry O’Neill’s chronicles were recovered from the old NDQSA.COM website files on 16 March 2024; and ‘the Battle at Widows Village’ _CPT Fleming 9thID article was recovered from 9th Infantry Division www.oldreliable.org/ 1980 Octofoil Journal during 2023 by RCBurmood

LZ Oasis _Daniel Ross-As I Recall Vietnam

Daniel Ross story with his memories of Vietnam. It includes a detailed account of the NVA attack on LZ Oasis on the night of 29 October 1970, and includes pictures of the damage.

Daniel Ross was on guard duty when the generator lights suddenly went out and a lone trip flair in the perimeter wire ignited. Within seconds there was firing and explosions from every direction INSIDE the compound. A well planned NVA assault was underway and multiple teams had made their way in and everyone was in deadly danger.

From his position in the guard tower over the Duster bunker Danny opened up with what he had at the muzzle flashes he saw. As he bent down to get another belt of ammo, the corner of the bunker above him exploded as a RPG found its mark.

Gary Oddi was the Executive Officer of H Battery (Searchlights), 29th Artillery stationed at Can Tho, Vietnam during 1971. The YouTube video is approximately 6 minutes and is a slide show of the pictures he took of the H/29th soldiers and their searchlights, primarily at Can Tho. During this time, H Battery (SLT), 29th Artillery provided searchlight operations in support of various airfields, MACV Teams, and Special Forces camps in Military Region IV.

(NDQSA film credits: Gary Oddi)

These units were spread from the DMZ to Saigon. They were used to guard LZ’s, run convoys, and search and destroy with infantry units. 1966-1972

(NDQSA film credits: Daniel Gallagher)

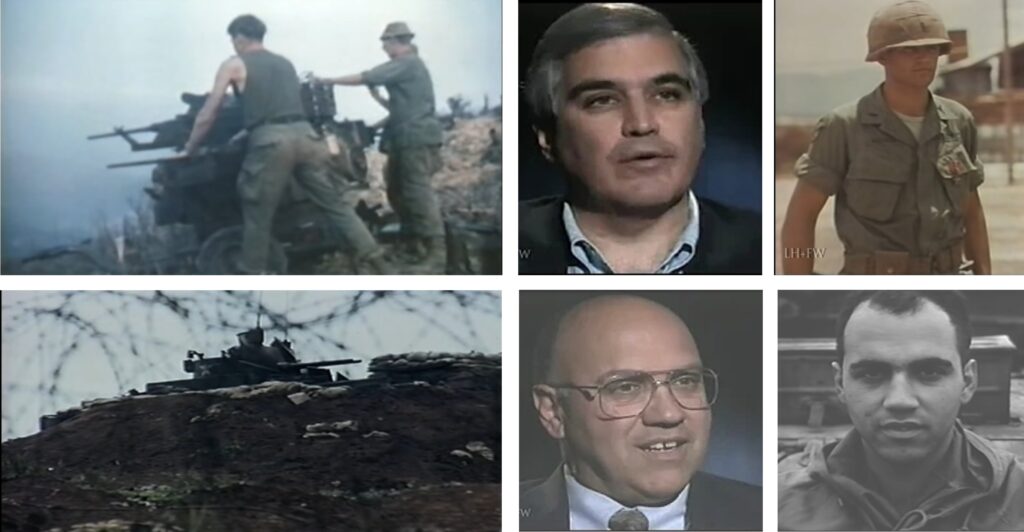

A superb set of documentaries, with each episode providing a different segment of the Vietnam war, as seen through the eyes of the veterans of the war. With excellent interviews and rare footage. Hosted by reporter and veteran Jack Smith. This is the episode: “Under Siege at Khe Sanh.” In early 1968 American troops found themselves pinned down in land locked combat base for 77 days. The marine base at Khe Sahn was ancient, isolated, desolate and divorced from reality. Under siege by the North Vietnamese bombs and rockets cascaded on the men below. Suddenly, there was no place to hide, no place was safe. “Death was measured in inches” said one soldier. This is the dramatic story of a daily routine punctuated by terror under constant fire, uncommon courage and unspoken heroism. This program includes historical footage and interviews with the people who know this story the best, the soldiers who fought it. This series first aired in October 1998 in six parts. Apologies for any technical issues with the picture or audio – this transfer was taken from an original VHS copy of the program. For education, entertainment, enlightenment and inspiration. We hope you enjoy and even learn something. Never forget! Courtesy of LionHeart FilmWorks

Chapters noted for the story of Dusters and Quads at Khe Sanh

Gun Positions 34:28

Snipers 35:21

Nothing would survive 37:26

The Men Left Behind 45:40

Interviews of Bruce Geiger at minute 34:30-35:40 talking about gun positions, the weapons and targeting. Includes video of Duster night firing and the Quad firing

then 37:00-37:30 about napalm strikes and devastation

Joe Belardo arrives as part of Operation Pegasus

43:18 Joe recalls ambush of Marine tank unit

45:57 Joe losing track of time as Khe Sanh is demolished by engineers to leave nothing behind

Bruce Geiger at 47:16 leaving by ground

Joe Belardo leaving 48:00 last track out of Khe Sanh

(Memo: NDQSA prep by RCBurmood)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.